Food Resiliency and Climate Change in the San Juan Islands

By Isara Greacen, Climate Communications Intern at LCLT. Photo courtesy Midnight’s Farm

“We’re a very long way from producing all of our own food. Right now, only around 3.5 to 4% of the food that’s purchased in San Juan County is grown here,” explains Faith Van De Putte from Midnight’s Farm who also serves as the county’s Agricultural Resource Committee Coordinator. In the San Juan Islands, food resiliency is a vital part of the livelihoods of our communites and it is more important than ever in the face of climate change. Despite the county’s small size, it offers a surprising abundance of local food resources. However, the community’s heavy dependence on imported food, much of which arrives via the ferry system, creates vulnerabilities. Currently, only a small fraction of the food consumed in the islands is grown locally.

Beyond the challenges that come along with the island’s isolated location, climate change is introducing new complexities to the food system. One significant impact is the influx of people moving to the islands to escape more extreme climates elsewhere—a form of climate migration that has the potential to reshape the food landscape. “The San Juan Islands look pretty good as far as climate risk,” says Van De Putte. “Smart people with the means are moving here.” This trend is “driving up real estate prices, which, in turn, affects land access and the ability to afford to farm here,” she adds.

As the San Juan Islands become a more attractive refuge from climate extremes, the local food system will face increasing pressure. “We’ll see more people move here and have more of the climate refugee situation,” Sage Dilts from Barn Owl Bakery predicts. This rising population could strain an already fragile food system, which, as Dilts points out, “is not really prepared for large-scale demand.”

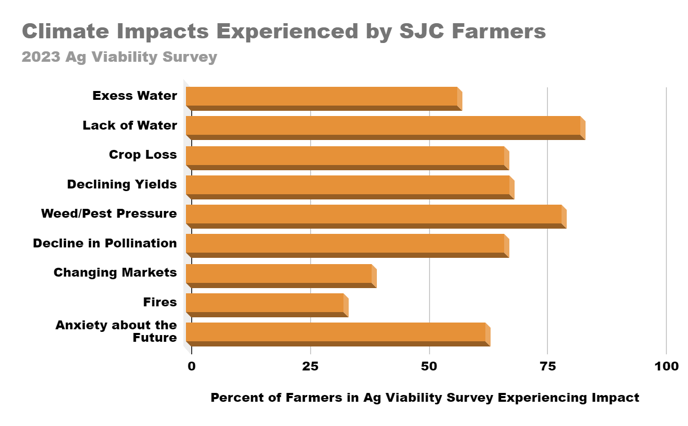

The changing climate itself is also creating new obstacles for agriculture in the islands. Farmers are facing wetter springs that delay planting and disrupt pollination, followed by hotter, drier summers that bring drought and the risk of total crop failures. Van De Putte recalls the devastating heat dome from three years ago, which led to multiple farms losing their entire crops. “Those kinds of events can have a very big impact,” she says. “The weakening Gulf Stream can influence anomalies like the cold we had this last winter. Anytime we go outside our normal bounds, there’s going to be effects,” Van De Putte adds.

Nathan Hodges of Barn Owl Bakery points out that it’s hard to prepare for such erratic conditions, “It’s really difficult to predict overall changes in weather patterns due to climate change.” Hodges and Dilts grow some of their own grain for the bakery and share that to mitigate this unpredictability, they focus on building diversity within their grain seed bank. “Rather than relying on one very productive monocrop that is genetically identical across all the individuals…we rely on thousands of genetically distinct individual plants and seeds, so that in any given year, there’s always going to be some plant that will do well,” he explains.

Dilts echoes this concern, noting that the lack of predictability is one of the biggest challenges facing farmers. “It’s not so much that there is a changing pattern, it’s more like there’s no pattern at all, and that’s the part that you need to have farming,” Dilts says. With the region showing trends of shifting towards wetter springs and drier summers, local farmers are adapting by looking to climates that have already experienced similar conditions. “We pivot and make some changes in our farming practices,” Dilt says.

In the face of these unpredictable and increasingly severe conditions, the need for a resilient food system has never been more critical. Van De Putte shares what resiliency looks like to her, “When I think about resiliency, I think about redundancy in systems.”Applying this to the food system in the islands, this means “having home gardens that are producing food, having a vibrant local agricultural community that’s producing food at a variety of scales, having the infrastructure that’s needed to process and store the food that’s grown here and distribute it, and then having the connections to the mainland and the ability to import food in different ways, through different channels,” Van De Putte explains. She highlights the importance of adaptability, stating, “Resiliency is the ability to respond to shocks to the system.”

Hodges and Dilts further emphasize the importance of localism and decentralized systems. Hodges notes, “Communities are the functional unit of a resilient food system…Over the long term, you have a much more stable food system than if you were just relying on a few large-scale farms.” Dilts echoes this, arguing for decentralized food systems: “The more you rely on one company to bring all the food over in a truck, one corporation to handle all the packaging and distribution, then you lose resilience.”

Recognizing these pillars of a resilient food system, San Juan County has already begun taking significant steps to enhance the resilience of its food system. The county stands out for its strong community values, innovative agricultural practices, and a deep-rooted commitment to sustainability. One key strength is the vibrant food culture that thrives in these islands. “We have quite a lot of people that have home gardens and are growing some bit of their own food,” says Van De Putte. “And we have a culture of pride in that.” This is evident in local traditions like community potlucks, where islanders eagerly share dishes made from ingredients they’ve grown or sourced locally. Dilts adds, “Lopez seems to have preserved or reclaimed a healthy food culture which values food as a livelihood and as a community gathering point.”

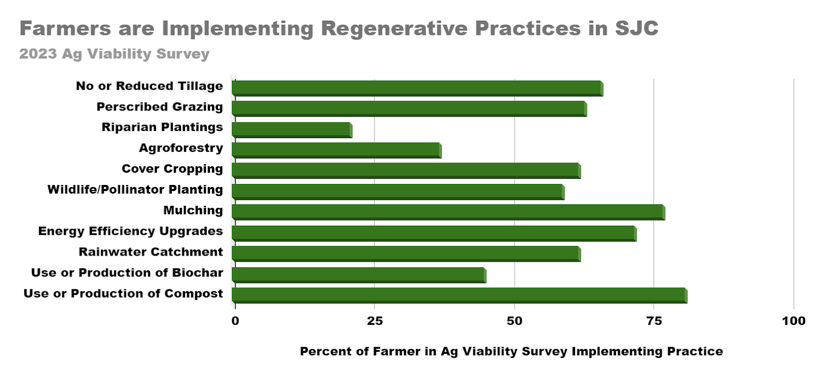

The quality of the food produced on the islands is another key strength. “The local food that’s grown here is excellent,” says Rhea Miller, Community Liaison for the Lopez Community Land Trust (LCLT). Midnight’s Farm is one example of a local food producer that pays a lot of attention to quality of food and sustainability. Van De Putte explains, “We compost, we practice regenerative agriculture… keeping the soil covered as much as possible, keeping a living root in the soil as much as possible and integrating animals.” These practices ensure that the land remains fertile and productive for future generations while also addressing concerns like wildfire risk through proactive forest management.

Hodges underscores the collaborative spirit that defines the county’s approach to food resiliency. “There are a lot of individuals, institutions, nonprofits, and government entities that have a lot of passion, interest and desire to build a very functional food system in the islands,” he says.

One example of a local organization that plays a crucial role in supporting the county’s agricultural sector is the Lopez Community Land Trust (LCLT). One of their landmark projects was the creation of the USDA-approved Mobile Processing Unit, which allowed farmers to process livestock locally. “We did the first ever USDA-approved mobile Slaughter Unit,” Miller recalls. Although the unit is no longer operating on the islands, it was a significant step forward for farmers to process their livestock locally.

LCLT has also developed a range of other programs designed to support local farmers and food producers. The Grain CSA, for example, allows island residents to subscribe to receive locally grown wheat berries every year. “People pay $24 for 20 pounds of wheat berries,” says Miller. “They pick it up in September, and there’s a miller on the island that can grind all of that 20 pounds or 40 pounds, whatever they want.”

LCLT provides access to farmland through three agricultural leases: Stonecrest Farm & Graziers, Still Light Farm, and Barn Owl Bakery & Heritage Grains. “We have nothing to do with their business,” explains Miller. “All we do is hold the land.” This arrangement allows farmers to focus on production without the financial burden of land ownership.

LCLT has also been instrumental in educational efforts, helping found the Lopez Island Farm Education (LIFE) program where Lopez School students learn hands-on about the local food system. “We co-founded the farm to school program so kids would understand the importance of local food,” says Miller. The program has since been taken in-house by the school, but its impact continues thanks to the support of generous donors and community members.

Lopez has many other food resources that I am not able to address at this time which also play an important role in improving food resiliency. These include: Taproot Community Kitchen, Locavores, the Family Resource Center, the Lopez Gleaners and more.

This being said, San Juan County’s food system, while resilient in many ways, faces a series of significant challenges. One pressing issue is the scarcity of water, which is essential for nearly all forms of agriculture. “Lack of water is definitely a concern,” says Faith Van De Putte, “when people think about agriculture, there’s a lot of things that you can’t grow unless you have water.”

Miller highlights the financial strain of farming on the islands due to poor soil health. “Since the ground isn’t fertile, there are things that you need to import… and so it just makes the cost of food a little higher.”

The high cost of land and labor further complicates the situation for farmers in the islands. Van De Putte explains, “Land access for new and beginning farmers is a huge challenge and is going to continue to be. When the value of the land is completely divorced from the productive value of the land, you can’t pay off land by farming it.” This disparity between land prices and agricultural viability makes it nearly impossible for new farmers to get started without significant external support. Additionally, the cost of labor is exacerbated by the island’s housing crisis. “It’s a challenge to find skilled people that want to work and to find housing,” Van De Putte adds. “If you don’t have housing on your own farm, where are they going to live?”

Isolation also plays a role in hindering the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of farming on the islands. “It’s challenging to access bigger agricultural production infrastructure,” notes David Bill from Midnight’s Farm, highlighting the difficulties of repairing equipment, sourcing inputs, and accessing other essential services that are more readily available on the mainland. Van De Putte agrees, pointing out that “on the mainland, you can get your tractor fixed, you can access all these inputs. So, our isolation and the ferries, that’s a weakness.”

Another major challenge is the seasonal nature of the island economy, which creates a fluctuating demand for local food. Nathan Hodges describes the difficulty of balancing the extremes between summer and winter. “In the winter, when it’s just locals, the demand for local food businesses and farms is very small, and then in the summer, there’s so much tourism… that the demand on all these farms and food businesses is so big that they can’t meet the demand.” This seasonal imbalance makes it difficult for farms and food businesses to maintain consistent operations, leading to staffing challenges and underperformance during the off-season.

Finally, the lack of an economy of scale is yet another challenge that increases the cost of locally produced food, making it less competitive with cheaper alternatives from the mainland. “We just don’t have the economy of scale that the mainland corporate food systems have,” says Sage Dilts. Without the benefits of subsidies and large-scale production, local farmers struggle to compete with the lower prices of corporate food systems. Even on the islands, where there is a strong culture of valuing local food, “people appreciate a good deal even if they have plenty of money,” Dilts notes, underscoring the financial challenges facing local producers.

To strengthen the resiliency of San Juan County’s food system, a multifaceted approach is needed—one that combines financial support, community education, and policy changes to support sustainable agriculture. Central to this strategy is the creation of grant programs designed to help local farmers overcome the unique challenges of island farming. Dilts emphasizes the importance of financial support, noting that “any programs that can reduce the prices for the consumer but keep the income the same for the producer are brilliant.” Such grants could help offset the high costs of land, labor, and inputs, making local food more accessible to both producers and consumers.

Hodges suggests that cooperative models could provide a solution for small farms struggling to stay afloat. “Running a small farm is incredibly challenging,” Hodges says. As farmers approach retirement, many find it difficult to pass their farms on to the next generation due to the financial and operational burdens. Hodges suggests that by establishing co-ops or centralized processing facilities, small farms could share resources and reduce individual workloads. “There has to be other containers in which the small farms exist in order to keep the continuity between generations,” he adds, stressing the need for collaborative solutions to ensure that farmland remains productive and doesn’t only get developed as residential real estate.

Education is another critical component of strengthening the local food system. With many newcomers to the islands coming from urban areas, especially with the onset of climate change, there’s a pressing need to educate people in the community about the benefits and opportunities of local food. “Once [people] move to Lopez, it’s up to us to help educate them to let them know where they’ve landed, that they have opportunities here that they don’t have in urban America,” says Miller. She suggests encouraging people to purchase local foods, educating why it is important to do so, and providing opportunities to teach people how to cook with fresh ingredients they may be unfamiliar with.

Supporting existing programs that are crucial to the community’s food system is also essential. The LIFE program mentioned above, which teaches Lopez students about local agriculture, is one such initiative that needs continued support. “The [LIFE] program was almost totally axed this year,” Miller warns, highlighting the fragility of this essential program due to budget constraints at the school. It was only saved by last-minute donations from generous community members. Ensuring stable funding for programs like LIFE is essential to maintaining the island’s food resiliency.

Finally, policy changes are needed to make land more accessible to new and beginning farmers. “Continuing to create pathways for land access for new and beginning farmers, continuing to provide education opportunities, and continuing to build supportive infrastructure” are key, according to Van De Putte. Miller also suggests that if landowners are to receive tax breaks for keeping land as farmland, they should be required to “provide adequate infrastructure like water and fencing and housing” for farmers who farm their land. “Zoning should be changed to allow farmers to have a place to live to keep farmland going,” she says.

As San Juan County faces the dual challenges of climate change and a growing population, the need for a resilient and sustainable food system has never been more urgent. By investing in local farmers through grants, educating the community about the benefits of local food, and continuing to support vital programs like the LIFE initiative, the islands can build a stronger, more adaptable food system. As Miller reminds us, “It’s up to us to help educate and support each other to ensure that our local food system thrives.” However the road ahead requires more than just practical solutions. We must come together, whether on the farm, as an island, or as a county, to face the challenges of our time. As Van De Putte says,”It’s a lot easier to be courageous with a community than to be alone in the face of climate change.”

Isara Greacen is a Climate Communications Intern for the Lopez Community Land Trust. She grew up on Lopez Island and now attends Scripps College.

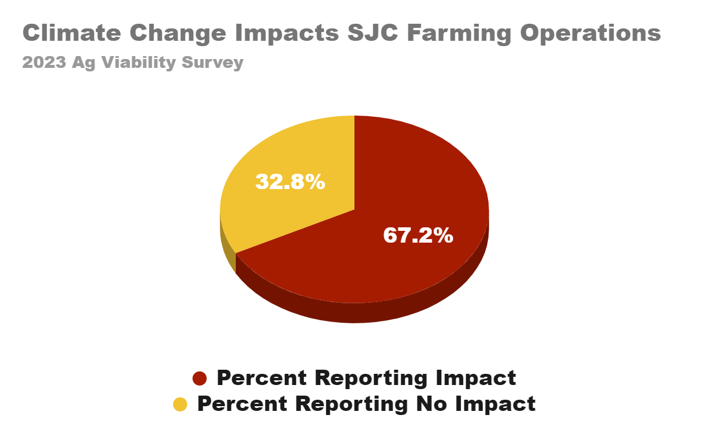

Results from the 2023 Ag Viability Survey below: